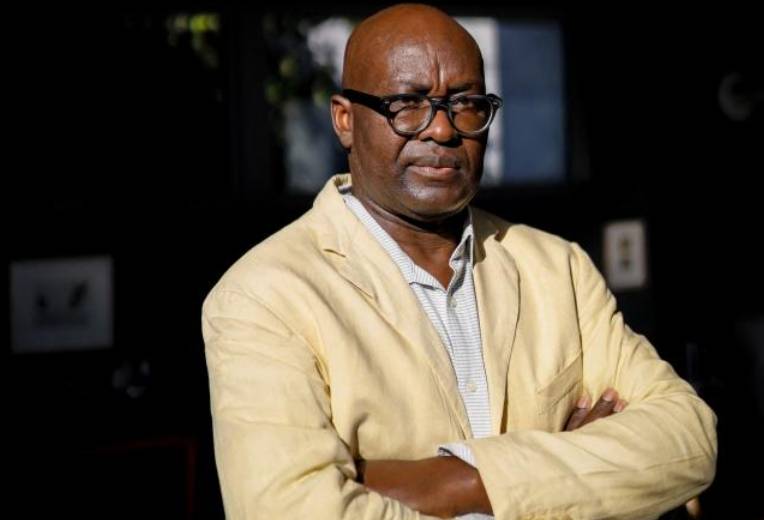

“The Earth Community” (La Découverte), the final book in a trilogy exploring Africa’s position in global discourse, has been published by a Cameroonian scholar.

During a brief visit to Paris, a Cameroonian scholar who is currently based in Johannesburg, South Africa, has taken the opportunity to increase his public engagements. His objectives during the visit are two-fold: promoting his latest book, “The Terrestrial Community” (published by La Découverte in February 2023), and advancing the Foundation for Innovation for Democracy, which he has been leading since November 2022.

“The Terrestrial Community” is the concluding installment of a trilogy that commenced in 2016 with “Politics of Enmity” and continued in 2020 with “Brutalism,” both published by La Découverte. The Cameroonian scholar has taken an organic approach in re-examining contemporary social, economic, and political challenges from an African perspective. In this final volume, he examines the prospects for a “common” in the context of the global environmental situation.

A reflective journey

“It all unfolded gradually. We open one window, enter through a door that leads to another, and eventually, a path emerges.”

“The Terrestrial Community” is the culmination of an intellectual journey that began in the 1980s, drawing philosophical inspirations from both the African continent and Europe and America.

“Until then, my focus had been primarily on the issue of identity, which I came across through African literature, especially the black poetry that emerged from the Négritude movement (Sédar Senghor, Césaire, Damas, and others). This literature sought to restore Africa’s identity and place in world history, to give Africa back its own face.”

Achille Mbembe believes that the issue of identity emerged in the philosophical field after the Second World War, in conjunction with the broader concept of the universal.

“We see it in the works of Levinas, Merleau-Ponty, Sartre. Modern African thought has also given it tremendous consideration, particularly in light of African history in modern times and historical episodes of domination such as the slave trade, colonization, and the continuation of racist regimes until the early 1990s.”

Starting in the 2000s, Achille Mbembe’s work as a philosopher and political scientist became focused on “the roots of this urge for separation – always with the goal of rediscovering what we have in common.” As in his previous works, “The Terrestrial Community” features a language that teems, searches for itself, and borrows from various sources. Its author is not afraid to introduce criticism and political analysis. One of the lessons that the scholar learned, among other things, during his time at Sciences Po, was from the renowned historian Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch.

Achille Mbembe’s self-aware and deliberate stance, “This is my journey, and that’s how it is,” is heavily influenced by geopolitical observations.

“The United States ranks third in my geographic hierarchy in terms of the black question.”

As someone who values the circulation of ideas, Mbembe is aware of the potential for manipulation. As a researcher at the prestigious University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, he sees this firsthand:

“There is a flow of concepts and categories between the United States and South Africa when it comes to experiences of race and racism, even though the historical experiences of North America and South Africa are profoundly different.”

Concepts to feed politics

Despite this, the intellectual does not shy away from delving into the twists and turns of thought, readings, and linguistic movements. For instance, a classic of Nigerian literature, “The Drunkard in the Bush” by Amos Tutuola, occasionally resurfaces in the author’s writing. Such borrowings demonstrate both a genuine openness to the world and a sharp political awareness.

In Mbembe’s thinking, rhetoric and politics are like twin siblings. His neologisms, organic writing, and focus on the living fuel vigorous criticism of capitalism and the technology-driven “computational” world. One concept that particularly interests him is that of the passer-by, which he qualifies through a funnel-like approach. First, he examines its philosophical meaning:

“It arises from the fact that we humans are only here for a short time. We exhaust our vital credit in the very act of dying.”

He then elaborates, punctuating his point with hand gestures:

“From this perspective, we do not own the Earth. Rather, it owns us by making room for us within it. This unconditional, extendable, and radical hospitality is the essence of the Earth.”

As Mbembe’s reflection deepens, its political implications become apparent. He views passing in its socio-historical sense, as a result of the great movement of migrations, both forced and voluntary. The concept takes on a political color in Mbembe’s language, as it implies the emergence of various encampment devices such as refugee camps, walls, and deadly border crossings. For Mbembe, the question of the government of migrations is a pressing issue, and it revolves around who has the right to live on the Earth, under what conditions, and how. He does not shy away from expressing his desire to see borders, especially intracontinental ones, abolished. Africa remains the anchor of his global thought, characterized by commitments, adaptations, and round trips. Mbembe stresses that Africa needs to open up to itself, and young Africans should not risk their lives crossing the Sahara and the Mediterranean. Africa is big enough to accommodate them, as long as it remains open.

A lucid intellectual positioning

The philosopher-political scientist, Mbembe, fosters openness on a personal level from South Africa, engaging in constant interactions with the global political and academic world. This unique positioning enables him to recognize the ongoing changes in the globalized intellectual landscape. He differentiates his approach from that of the neo-Pan-Africanists who seek to locate the continent’s misfortunes outside it. Mbembe’s realism avoids nihilism and cynicism and emphasizes a relatively poetic dimension in his work. He identifies two harmful illusions in the current understanding of Africa’s challenges: libertarianism and neo-Pan-Africanism. Mbembe advocates for a collective intelligence rooted in concern for the living as the essence of democracy and the capacity to mobilize.

With a concise statement, Mbembe encapsulates the ambition of his most recent book:

“I am advocating for an Africa that is open, borderless, and democratic.”

Does the completion of his trilogy of written works mark the start of political engagement through both words and actions? The answer to this question remains uncertain as the discussion transitions to a new topic.